A Journey of Love and Faith – Nikki and Adam’s Foster Care Story

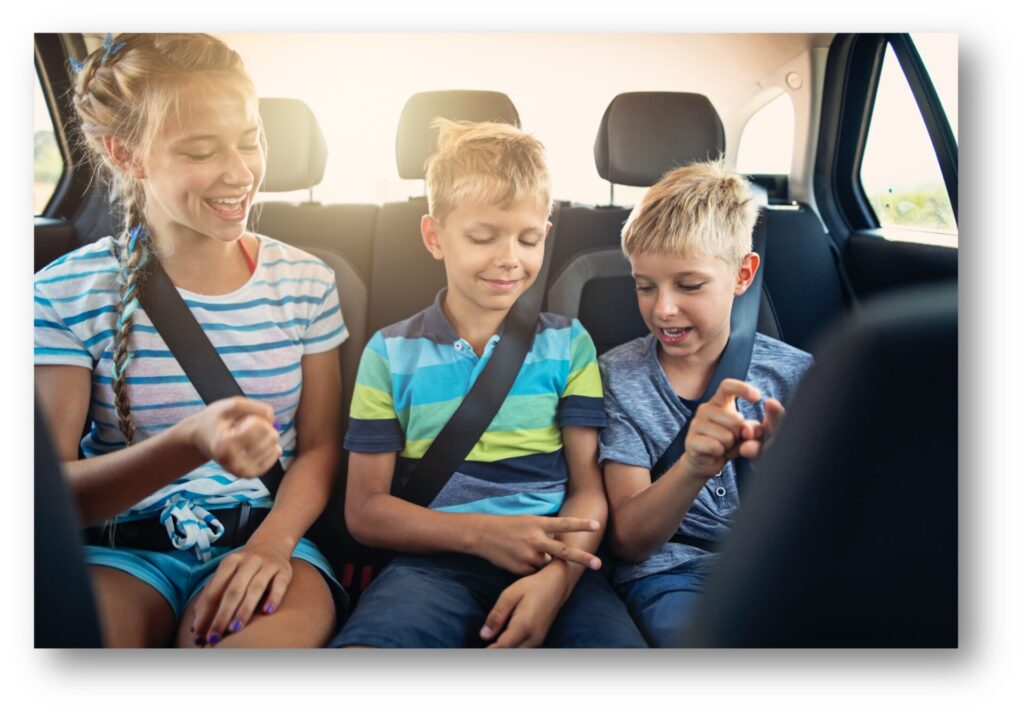

By: Brooke Rouse, BA, Marketing Manager When Nikki and Adam first dreamed of growing their family, they imagined adoption—not foster care. “Funny story,” Nikki says with a smile. “We knew we wanted to adopt, and years ago, I even spent a summer working in an orphanage in Romania.” With two biological children already, they attended a large seminar filled with adoption agencies. Foster care wasn’t on their radar. “We were sure we didn’t want to foster,” Nikki recalls. Their adoption journey eventually led them to China, where they welcomed their son into their family. Life was full and beautiful, but God had more in store. “We walked into Beech Acres thinking about adoption again, kids whose parental rights had already been terminated,” Nikki explains. “But God put it on our hearts to walk with biological families, too.” That shift changed everything. They joined the foster care program at Beech Acres Parenting Center (BAPC), and for the past four years, they’ve opened their home to sibling placements and provided respite care for other foster families. Along the way, they’ve built incredible relationships with biological families, something Nikki calls “a privilege.” Their first placement was unforgettable: premature twins who spent months in the NICU. “We have twins on both sides of our family, so we thought it was really special,” Nikki says. But the reality was challenging. The babies were medically fragile and needed constant care. “Failure to thrive, feeding issues. There was so much to learn,” Nikki shares. Yet her biological kids embraced the babies wholeheartedly, and Nikki formed a close bond with their grandmother. “We still talk twice a month,” she says. “It was an amazing experience.” Nikki even helped the grandmother and eight siblings move into a new home, making sure they had Christmas gifts and everything they needed. Her second placement brought more joy – and more challenges – with three four-year-olds and a three-year-old, all with medical needs. Through it all, Nikki’s strength has been advocacy: “I fight for my kids. That’s my role.” Beech Acres has been a constant source of support. “From the very beginning, they’ve gone above and beyond,” Nikki says. When the county wouldn’t allow her to visit one of the babies in the NICU, BAPC stepped in. “Even the CEO called to advocate for us,” Nikki recalls. “They never stop fighting for families.” Fostering has taught Nikki something profound: “I’m capable of loving kids instantly.” Her family is beautifully diverse, with African American, Chinese, and Hispanic children. “It’s a privilege to love these babies,” she says. “I’m more protective and stronger than I ever imagined. I never thought I could handle medical needs, but now I know I can.” Building trust starts with the basics: food, safety, and play. “Adam is the fun one,” Nikki laughs. “He gets down on their level, plays, and makes them laugh.” For Nikki, it’s about creating a nurturing environment where kids feel secure and loved. “Our kids are the biggest love bugs,” she says. Her advice for anyone considering fostering? “You can do it, you just have to jump in,” Nikki says honestly. “The first two weeks, you’ll wonder if you made a mistake. But with a support system, you’ll get through it. We didn’t cook dinner for two weeks because friends and church stepped in.” She recommends reading trauma-informed books and leaning on community. “Once those kids walk through your door, you love them. I choose to do the hard things because they don’t have a choice. If not me, who? If not now, when?” One memory stands out: her current placement of siblings, ages three and four. “Little moments – like when our three-year-old started talking – are everything,” Nikki says. “Kids who’ve been through trauma are still capable of love. They can soften and tender. Seeing that transformation is incredible.” Adoption and fostering have shaped Nikki and Adam’s family in ways they never expected. “We said ‘no’ to certain needs at first,” Nikki admits. “But when those kids became ours, none of that mattered. You love them with all your heart.”